Timeline

The principal at East High School removes a sign from a Black History Week display & students cannot attend class. Classes at Franklin Junior High School are dismissed after several hundred Black community leaders protest the removal of a Columbus Metropolitan Area Community Action employee who counseled students who were potential dropouts (Black student enrollment is 97%).

Mohawk Junior High prepares a one-day celebration for Black History Week

School was closed early the previous week due to “riotous conditions” after a Black History Week sign was removed. Bombs had been set off in lockers and numerous fires started. During a PTA meeting, 730 black and white parents favored stricter discipline. Principal requests teachers be more rigid with applying discipline and a plan is developed to expel non-compliant students. Some parents believe racial problems were the catalyst for the disorder, but teachers insisted it was simply disciplinary. At West HS, a group of black students asked for a minute of silence for Malcolm X; the request was denied.

Teachers raise concern about racial disorder that arose after white students walked out of a Black history week program featuring a Black poet.

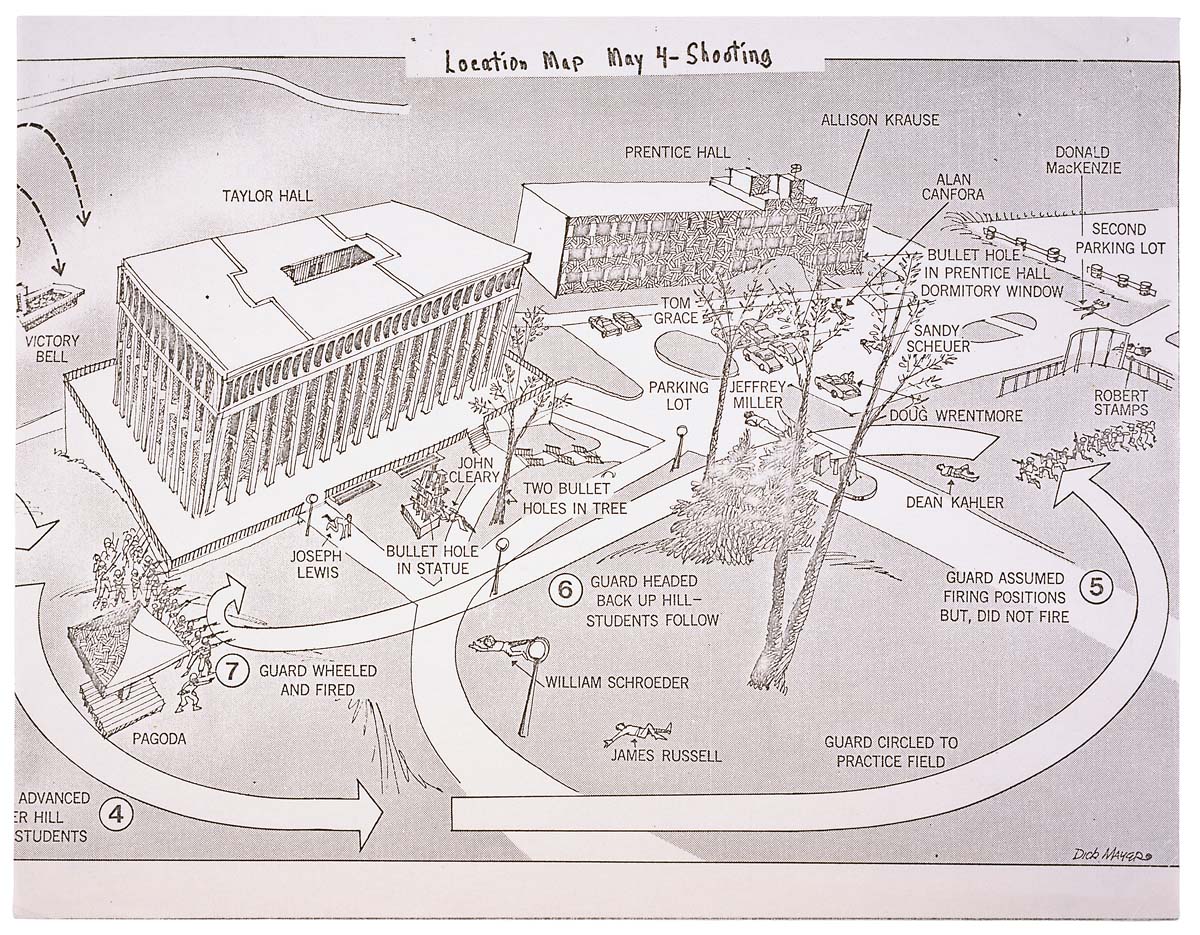

The Ohio National Guard kills four and wounds nine unarmed students at Kent State University during a Vietnam War protest.

Two students are killed and twelve are injured during a “28-second fusillade” by state highway patrolmen outside of a dormitory.

East High School partners with the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) to host two “Black-oriented” cultural programs.

Coordinated by ASALH, OSU will celebrate United Black World Week.

For the third year, St. John's AME Church sponsors a Black History Week program, spotlighting pioneer Black educators.

Nommo X, leader of the black nationalist organization Afro Set, spoke at Mohawk Junior-Senior HS. Parents complained that he forced students to stand and pledge allegiance to the black nationalist flag (68% of Mohawk students are black).

Black students left a “patriotic assembly” and were disgruntled that the school was not recognizing Black History Week. The fire alarm was pulled that afternoon.

At Linden McKinley, four white students dropped “anti-black literature” from the balcony of the auditorium to the main floor during a Black History Week assembly; fights broke out. Problems related to assemblies at West HS, Mohawk HS, and Central HS also occurred.

Duane Reed, principal at LMHS, reported that four white students who threw racist propaganda flyers during an assembly were suspended; further action was up to school officials. West HS suspended four students and Central HS continued meetings with students. No action taken at South HS and Hilltonia JHS.

A controversial assembly featuring OSU Professor Charles Ross at Worthington HS was praised by many of the over 100 attendees.

Columbus Board of Education unanimously approves resolution for maintaining discipline; the lack of “Negro history studies” is cited as one cause of student unrest.

A letter to the editor proposes a more inclusive and accurate American history textbook would eliminate the need for Black History Week.

Black residents and administrators weigh in on Black History Week; Clifford Tyree denounces it and wants an integrated curriculum, Roger Germany agrees and notes school officials have ignored student demands, Will Anderson reports no problems at almost entirely Black Linmoor JHS, and Frank Watson believes students aren't as prejudiced as their parents.

Superintendent Harold Eibling promises to address demands of 500 Black protestors and create a special task force; he plans to complain about WVKO radio station Les Brown's announcement that encouraged protest. Parents raise concerns about school punishment racial disparities, racism in schools, and disrespect toward Black parents and Black educators. Approximately 1200 of the 1800 students at LMHS aren't in school; the other 600 meet with teachers to discuss recent problems.

An editorial that denounces Black history and affirmative action declares “Black-oriented” groups are racist. Gives examples of Black men like Thurgood Marshall who are no longer Black but are now “outstanding Americans.”

In editorial, a late 1950s East HS alum notes there were no racial disturbances then, but Black girls could not be cheerleaders and very few Black boys made athletic teams. Opposes Black History Week because it's too short. Believes the riot squad incited the disturbances, not Les Brown.

An editorial from '61 alumna of North HS. North had a few hundred Blacks then and everyone got along. Claims she was not raised to be prejudiced, but questions why she should teach her children Blacks are equal to whites, and believes protesters are prejudiced against whites and ruining white respect for Blacks.

An editorial in support of strong force being used against “troublemakers” draws on “guerilla war” analogy to advocate for confinement.

Twenty-five parents signed a letter urging Worthington School Board to scrutinize assembly speakers. Members of the Worthington Women’s Club accuse Black History Week speaker Professor Charles Ross of being a safety concern for students.

LMHS assistant principals Thomas Brown and Terry Steele, Columbus Community Relations Director, Clifford Tyree, and Thomas Giles, President of the Columbus Education Association, study allegations of racism in Columbus Public Schools. Their sub-committee made proposal to divide district up; no action was taken by the task force.

William Kunstler urged 600 Bowling Green University students to abolish ROTC on campus, calling it a “work of death” that “is the antithesis of the academic community.”

Approximately 200 hundred “Negro” adults and children attended a program in Franklin Park to commemorate the birthday of the late Malcolm X. Professor Charles Ross, director of Black Studies at OSU, played one of Malcolm’s speeches; Rev. Arthur Zebbs encouraged teaching Malcolm’s life in schools; and Alex Haley is scheduled to speak at the evening memorial. The program ended with a motorcade through the East Side.

After the Malcolm X observance at LMHS, black students wandered halls and school grounds and most white students went home; no reports of violence. The Columbus Board of Education was informed that on Tuesday (May 18) LMHS students lowered the American flag and trampled on it.

Malcolm X event at Franklin Park was organized by Professor Charles Ross and included speeches, music, poetry, a parade, and speech by Ross and Alex Haley. A group of LMHS students marched from LMHS down Cleveland Avenue to the park after an observance at their school that included reading speeches by Malcolm X; many white students went home. Black students had taken down the U.S. flag but firemen put it back up.

A white OSU student who rode his motorcycle to the park to hear Haley speak was hit with a bottle and kicked by five or six blacks, and his motorcycle was set on fire. A police officer said a Black Vanguard member burned his ear with a flare.

White reporters were told to leave the park despite Ross promising all were welcome.

At 7pm a caravan of more than 200 cars—many with blacks sitting on car hoods and roofs—left the park without heeding police direction. The caravan was led by a color guard carrying Black nationalist flags. The caravan collected 3,000 people on its route through the East Side and back to the park. Rain at 10:30pm broke up the event.

OSU indicated they would look into the role Ross played in the event and determine if there was a concern.

A 19-year-old white man was hospitalized after surgery for a head injury reportedly caused by being jumped by 12-15 black students when he was dropping off a friend at LMHS during a Malcolm X observance.

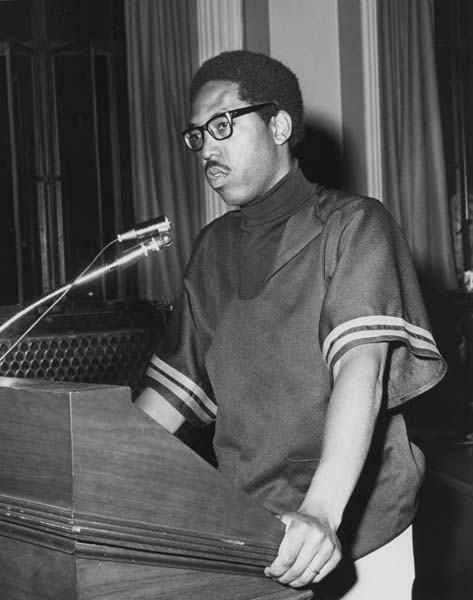

Professor Charles Ross is known as a militant. He was unavailable to comment on events stemming from the Malcolm X birthday observance. A memo on Ross’s OSU letterhead announced a meeting at the Harambee Center last Friday (May 14) to discuss plans for the event.

During the observance, three Dispatch reporter-photographers were ordered to leave the park; a young white man was beaten and his motorcycle burned; and a plainclothes white police officer was burned when a black youth jabbed him with a flare.

The police reported minor city ordinance violations, but police stayed out of the park to avoid confrontation.

After a school assembly honoring Malcolm X, approximately 200 black students from “troubled” LMHS marched to the park and some carried black, red, and green black nationalist flags. A white youth was beaten by a gang of black teenagers near the school during the assembly.

Superintendent Eibling said the assembly at LMHS did not violate his previous order that disallows outside speakers in individual classrooms or small group discussions.

Superintendent Eibling promised six white students that only the American flag would be flown outside of schools and on auditorium stages after the displaying of the black nationalist flag led to LMHS closing on Thursday (May 20). The six white students were chosen as representatives for 100-200 white students from LMHS and McGuffey JHS; they were transported by police motorcade to the central administrative offices after LMHS closed.

Controversy started on Tuesday (May 18) when the black nationalist flag was raised on the flagpole in front of the school. When school opened on Thursday (May 20), a group of white students noticed the black nationalist flags in two stands on the auditorium stage. White students asked assistant principal Thomas Brown to remove them. The white student coalition reported to Eibling that Mr. Brown kept responding “What?” to their requests. The white coalition wanted assurance they could attend school safely and only the American flag would be displayed at school. The students also said three photos of former LMHS principals were removed by students.

Eibling says only American and Ohio flags can be flown at Columbus Public School buildings. This policy came after a special LMHS faculty meeting on Thursday (May 20) in which teachers voted to allow the black nationalist flag to fly alongside the American flag. Eibling says LMHS will reopen on Monday (May 24) with “adequate security.” Eibling emphasized teachers would comply or be subject to disciplinary action.

Principal Duane Reed recommends not reopening LMHS on Monday (May 24). LMHS faculty met on Saturday to discuss school issues and felt tensions were still too high. While LMHS faculty had voted to allow the black nationalist flag to be displayed, Superintendent Eibling, backed by the school board, says the American and Ohio flag are only allowed to be displayed: “I can’t surrender on the point of the flag; there is only one flag for the American people.”

Eibling says LMHS will reopen on Tuesday (May 25) for all students. LMHS closed before noon on Thursday (May 20). Eibling reported that a group claiming to be LMHS alumni said they would tear down the black nationalist flag if it was allowed to be displayed in the building.

At West HS a group of approximately 25 Negro students marched into the school auditorium with a black nationalist flag; school officials removed the students from school.

Classes resumed for the first time since the school closed on Thursday (May 20). All available police were dispatched; 30 police with clubs herded students down hallways after the principal ordered them to class or be arrested. A white student was beaten by approximately 10 black students in a hallway; no arrests were made. Police confiscated a 14-inch pipe they believe was used in the beating. A different white student said he was hit in the eye by a Negro student and taken to the school office.

At West HS, 20 students were suspended after marching into the school auditorium on Monday (May 24) with the black nationalist flag. A suspended student was removed from school property after trying to enter the building with a black nationalist flag attached to a pole.

92 LMHS teachers (15 who are black) voted to allow the black nationalist flag to be displayed.

Two McGuffey JHS students were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct; one tried to get 25-30 black students to a fight a white youth and the other was spotted by police with a wooden club, which he tried to hit a police officer with.

Every room at McGuffey was ransacked, resulting in vandalism damage of around $2,000.

Dispatch had hard time tracking down the history of the flag. The library had no information. The spokesman for OSU Black Studies didn’t wish to comment. The article explains that the black nationalist flag has had many meanings and designs since its creation a half a century earlier, but the colors red, green, and black have remained as Marcus Garvey designated them in 1920 in “Declaration of the Rights of Black People of the Earth.” Then director of the Flag Research Center in Massachusetts provided the history. Local blacks have interpreted the colors as black represents the soil of the land or black power, green represents money or economic value blacks have never had, but red is consistent in all interpretations as blood.

Superintendent Eibling and city officials devise a plan that might allow LMHS to reopen. LMHS closed Tuesday (May 25) for the second time in a week due to racial unrest. There is speculation over how and if 433 seniors can graduate. LMHS was closed around 11am on Tuesday after a black nationalist flag was displayed on the stage and many students refused to obey Principal Duane Reed’s order to attend class. 11 LMHS students, 2 school employees (Wesley Greenfield and David L.Paige), and Charles Ross were arrested at the school. A school spokesman said contrary to reports, Ross had not been invited to LMHS, there was no planned program, and Ross’s appearance was unexpected by administrators. The school was closed Thursday afternoon (May 20), and all day Friday (May 21) and Monday (May 24) It reopened Tuesday with the American flag on the pole in front of the building. At around 10am on Tuesday a group of students placed a black nationalist flag on the stage in the auditorium.

About 50 students at Hilltonia JHS refused to return to class after a scheduled assembly.

A woman reported to police that while driving down Duxberry near Cleveland Avenue she was stopped by armed youth with clubs who knocked out her windshield and struck her on the shoulders and back.

Ross has a salary of $24,500 and has been a central figure in “racial turmoil” at LMHS and other schools. University officials would not comment, but it is “known” that they are dissatisfied with his conduct. Multiple school disturbances occurred after he organized the Malcolm X memorial, including racial fights and firebombs.

Late on Tuesday (May 25) evening a crowd of approximately 500 blacks marched from Cleveland Avenue to LMHS and raised the black nationalist flag around 10:15pm.

At least a dozen young blacks pulled automobiles into intersections around the school, removed ignition wires from the vehicles and left them to block traffic. 24 police in full riot gear formed on Duxberry Avenue. Rain eventually sent the youth home and patrolmen enforced an 11pm curfew.

Policemen tried to take down the flag but were stumped when they discovered the flagpole rope had been tied to the roof. Police dispatchers received numerous angry calls about the “banner”—one caller threatened to go to the school with friends and shotguns and remove it if the police did not. Police finally called a janitor after 11pm and had him remove the flag.

Sgt. Marvin Muncie said the most serious charge filed against Ross was interfering at the scene of an emergency. It was an emergency because C and D platoons had been called to duty.

Ross was offered the OSU position in April 1970 while he was an assistant professor at the University of Chicago and an Indiana Congressional candidate. He accepted the position after he was defeated in the primary.

Ross was hired as an associate professor at OSU and granted tenure, which was unusual but not unprecedented.

16 juveniles were arrested during the Tuesday disturbances; most were released to the custody of their parents. One parent refused to accept responsibility for his son, who was held in a juvenile detention home overnight.

There will be “strong police protection” at “strife-torn” LMHS when it reopens for only seniors to take their exams. Police and school officials have “special plan” for any disruptions.

Three high schools will have 24-hour police guard duty: LMHS, Linmoor JHS, and McGuffey JHS. 12 patrolmen, two sergeants, and one lieutenant were placed at LMHS

Off-duty police personnel will work inside the school building at the school system's expense but be under the command of the police chief.

Numerous students at various junior high schools were arrested, arraigned, or had hearings for assault, vandalism, and school disturbances.

More than 30 city police and East Side Security Patrol officers are on duty in nine buildings.

CPS began hiring “the protection” March 1 after racial incidents closed Central HS.

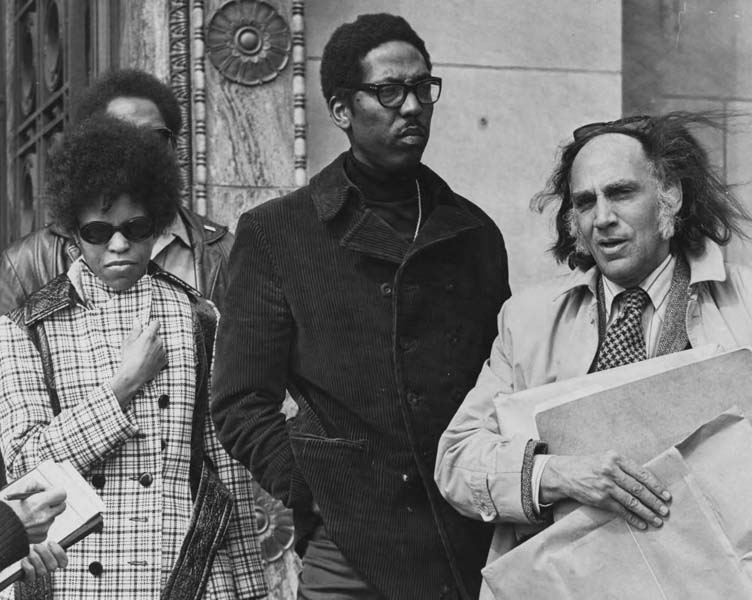

William Kunstler will represent Charles O. Ross at a university hearing. Kunstler gained national fame when defending the “Chicago Seven.” Ross was arrested last Tuesday (May 25) by Columbus Safety Director James Hughes at LMHS during disruptions that forced the closing of the school. Ross was charged with failure to depart, assault, and interference at the scene of an emergency; he also scuffled with a police officer. Ross was also charged with violating provisions of a state campus disruption law. Kunstler insists Ohio House Bill 1219 is unconstitutional. The bill allows for suspension of any student or faculty member involved in violent acts. A group of white OSU students organized a march in support of Ross. Dr. Kelsey, also an OSU faculty, accompanied Ross at LMHS and both report being “accosted by a patrolman.” Kelsey was not arrested.

11 LMHS students were arrested during the “demonstration” Tuesday; they entered innocent pleas on an assortment of charges.

Columbus chapters of NAACP and Urban League call on public to halt school disruptions, emphasizing the value of education.

50 witnesses subpoenaed to testify on behalf of Charles O. Ross, including President Novice Fawcett. Ross is the first official at a state-supported university charged under provisions of the one-year-old House Bill 1219. At the university hearing, Ross could be suspended from his job or could be exonerated

250 OSU students demonstrated on Ross's behalf.

Dr. Kelsey states the media reporting of events at LMHS are inaccurate and it is part of the university's “get-Ross” campaign that extends throughout the city.

Wesley Greenfield, a school custodian, was charged with using improper language and disorderly conduct, and David L. Paige, 21-year-old “home community agent” for the school, was charged with failure to depart and using obscene language both pled innocent.

Eastmoor HS principal Kenneth N. Olbert reports racial problems escalate after Ross’s January 14, 1971 appearance there, citing example of the evening after Ross’s speech a group of 20-25 black males were trying to “crash the gate” at a basketball game. Olbert claims the boys ran when he approached and yelled “Ross will take care of you.” That evening there were several assaults involving black and white students. Olbert testified that progress toward integration was happening prior to Ross sharing black separatist and nationalist ideologies.

Kunstler’s defense team claims Ross is the target of a planned police and university effort to oust him from his $24,5000 OSU job. John Elam, OSU’s attorney, claims Ross planned his own arrest on May 25th at LMHS when the school attempted to reopen after closing five days earlier. Elam claimed Ross met with black LMHS students in his OSU office on May 24 and encouraged them to display the black nationalist flag at school. Ross refused to testify.

Ross hearing had tight security. Kunstler had a six-man team. Legal counsel for OSU and prosecutor of Ross was John C. Elam of Vorys, Sater, Seymour, and Pease. It was alleged that during fingerprinting at the police station Ross balled his fist and cocked his arm at an officer. Elam stated, “Racism can work both ways...The flying of that (black nationalist) flag at the (Linden McKinley) school had the same impact on the white students as if a Columbus white group were to fly the Ku Klux Klan or Confederate Flag...It was equally disruptive…”

Olbert testifies and emphasizes Ross’s association with the Black Vanguard that he started in January 1971 and worked to form a coalition with OSU’s Afro-Am and the East Side Afro Set.

Ross’s 3 and 7 year old sons were present, and Ross wore a dashiki.

Police chief Hughes testifies there was pandemonium at LMHS when he arrived at 10:30am on May 25. He claims there were approximately 50 “outsiders” in the school and that Ross said something to the effect of he'd start a riot. Ross refused to leave and asserted his right to be there.

Professor Richard Kelsey was the only witness called for the defense. He said he and Ross arrived at LMHS around 10:15am after hearing there was “trouble.” They went to “pacify” the situation. He said they left the auditorium when Principal Reed announced all outsiders must leave the building. Then Kelsey noticed Ross was no longer with him. He looked around and saw two police officers holding Ross. Kelsey said students in the auditorium were not noisy and disruptive as described by other witnesses.

An assistant principal, two teachers, three students, and two other people were arrested on Monday (June 7) stemming from brief clashes with police. Incidents occurred on the next to the last day of final exams scheduled after disorders closed Linden McKinley HS on May 20 and again on May 25.

John Farley (23) and Christina Voyles (25)—both teachers at Linden McKinley HS—request jury trials for charges of interfering with police. Assistant Principal Thomas Brown (34) requests a record hearing for charges of disorderly conduct, assault and battery on a policeman, resisting arrest and making menacing threats.

Ohio State University officially removed Professor Charles Ross from directorship of the Black Studies program, a $24,500 position, for “unsatisfactory administrative performance” without mention of Linden McKinley. He will continue at OSU as an associate professor of Social Work. Two weeks prior, a special hearing officer for the university dismissed OSU proceedings against Ross related to his May 25, 1971 arrest at Linden McKinley HS. Ross pleaded innocent to city charges; municipal court date set for June 25.

OSU special hearing officer dismissed charges because off-campus activities cannot be construed as campus disruption. Ross did not testify during OSU hearing. He intends to appeal his directorship dismissal.

Wesley Greenfield, a janitor at Linden McKinley HS, appeared in municipal court on disorderly conduct and improper language charges related to disturbances at Linden on May 25.

Two black administrators are named as principals at “racially troubled” Linden McKinley HS and Mohawk Jr-Sr HS.

The mayor proposed a committee to help neutralize student disruptions; board tentatively accepted.

Linden McKinley HS assistant principal arrested during “disruptions” is transferred to same position at Southmoor Jr. HS.

After going to the aid of black assistant principal Tom Brown who was being attacked by police, a white first-year social studies teacher, John R. Farley was arrested. The jury composed of 9 women and 3 men heard testimony for the prosecution from three Columbus police officers that Farley interfered when they were trying to arrest Brown by grabbing officers' shoulders and ankles. Brown testified he was confronted by police and shoved and then beaten with nightsticks—15-20 strikes. Curtis Smith, a Linden teacher, testified Farley did not grab officers but slid between them. Farley testified Brown shoved a police officer after being shoved by the officer.

Due to a hung jury, a mistrial is called in Farley’s hearing. Four jurors were black. A new trial will be scheduled later. Farley and Brown are not on the Linden McKinley HS school roster for fall.

Assistant principal Tom Brown was charged with four misdemeanors--disorderly conduct, assault and battery on a policeman, resisting arrest, and making menacing threats. The event occurred June 7 during “racial disturbances” when seniors were taking final exams.

The judge dismissed the menacing threat charge, but denied the defense's motion to dismiss three other charges. The jury was composed of 10 women and 2 men. Several white teachers witnessed the incident and confirmed Brown's story that police officers beat him with night sticks 15-20 times on the arms, back and head; the teachers' stories varied only as to how many officers were involved.

Brown holds three college degrees and was a military officer. He has worked 10 years in the Columbus school system.

Brown's Account: during early afternoon on June 7, he was in his office and had taken off his suit jacket which the ID badge was attached to. While in his office he heard a scream; police had arrested a student's mother and she was screaming that she had a heart condition and had chest pain. She asked Brown to inform her son, so he would not hear second hand. Brown went hunting for her son, who was six feet tall and 220 pounds. While on the stairwell between the second and third floor Brown was confronted by a police officer who asked for his ID badge. Brown identified himself as an assistant principal and said his badge was on his coat in his office. The officer jabbed him on the shoulder roughly and continued questioning him. Brown tried to walk around the officer and was elbowed in his side. Brown began to sob on the stand. He said he was pushed against a wall and when he bounced off he pushed the officer in self-defense. Several teachers testified hearing officers saying to put down everything for charges and let the court or downtown figure it out.

Wesley Greenfield, a Linden McKinley HS custodian, who was acquitted of charges the previous month, is expected to attend an open meeting of the Columbus Custodial Chapter. Greenfield plead innocent on all charges. He was released on $200 bond on the obscene language count (for using obscene language in the presence of females).

Community Relations Director, Clifford Tyree, believes Black History Week “should be done away with.” He considers one week per year to be a “token gesture.” He claims it promotes racial tension in the schools, as well as fear.

He prefers that black history by taught in schools year-round, either as an elective or required. He supports the NAACP lobbying for a state law requiring a black history course in all Ohio high schools. He refuses to participate in any Black History Week programs at schools.

Columbus Community Relations representatives and the city's school system agreed that black history week observances should be dropped. Clifford Tyree says the programs have created tensions. Tyree recommended black history studies be integrated into regular school studies.

Columbus School Board approves recommendation to intensify hiring of black teachers. Board also approved 57 other suggestions submitted by the Project Unite study. Board approved continuing its policy of assigning minority staff to improve racial balance. Project Unite recommended moving away from a Black History Week and to instead develop an integrated curriculum. Board approved a recommendation to obtain high quality teachers and eliminate unqualified teachers. Board called for career education and elimination of “sex barriers” in vocational courses.

Franklin County Court of Appeals ruled Tuesday (June 8) that a jury trial cannot be waived after it learned the jury is deadlocked. Mrs. Christina Voyles, a teacher and student counselor, at LMHS was arrested June 7, 1971 during a disturbance at the school when she interceded on behalf of vice principal Thomas Brown as he was being arrested. She was charged with resisting and obstructing a police officer in the discharge of his duties.

A class action lawsuit originally brought before Court in 1973 and decided for plaintiffs. Nine Columbus Public School students were the plaintiffs. The cause of action was the school district suspending students without first holding a hearing. The suspensions arose out of widespread racial unrest among students in February and March 1971. The issue was whether suspension without hearing violated the students' Due Process protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court held in favor of the students and on appeal the United States Supreme Court upheld the holding. Black Studies, memorials for Malcolm X, and general racial tensions spurred most of the suspensions.

This class action lawsuit was brought to the Ohio District Court in 1973. The Court held that Columbus Public Schools practiced de jure segregation and had not heeded the holding in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and was, therefore, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

On appeal, the United States Supreme Court upheld the holding for the plaintiffs. The legal method of redress was to utilize busing to integrate Columbus Public Schools. *Preemptive to the Court's decision, the “alternative” school system was a grassroots teacher and parent initiative to voluntarily integrate. Columbus Alternative High School was the first alternative school and due to its success and popularity, numerous others would follow shortly thereafter.